Toei, In-betweening, Tezuka, Labor Movements and Rintaro

They’re very valuable testimony about the reason for the high salaries in Mushi Production at the time of Osamu Tezuka, the working conditions of the anime industry at the time, and the relationship between anime and social movements.

After working as an animator in a few commercial production companies, Rintaro got hired in Toei and was given the management position of the colouring area.

Being a manager in this area, which had a high ratio of female workers, he eventually passed the required tests inside the company to become an in-betweener. He also became friends with Sadao Tsukioka and Gisaburo Sugii at this time. However, he started feeling his limit as an animator and decided to pursue the director position.

He gathered some courage and asked the Toei’s production department, but got rejected by the director Daisaku Shirakawa2:

Basically, if you didn’t manage to get hired as a full-time employee in Toei right after graduating university back then, you couldn’t become part of the direction department. Both me and Gisaburo Sugii were just temporary workers at Toei, that’s why I got rejected.

Even though I played around a lot back then, I still had to pay rent and I didn’t even have money for food. My monthly salary was about ¥5,000 after all. On the other hand, the salary of university graduates was about ¥12,000 I think. The gap was evident.

Those who gave up the path to becoming an episode director were already included in a blacklist inside the company, so they started fooling around even more. It’s also said that many sold their meal tickets of the staff cafeteria (given to them as advanced payment) in exchange for money for cigarettes.

The frustration kept piling up, and looking for an outlet they eventually became involved with the labor movement of that time. He talked about their experience with the 1960’s Toei labor movement, and their close connection with the protests and conflicts related to the US-Japan Security Treaty at the time3:

Back then there was the problem of the US-Japan Security Treaty4 in the 60s. Even inside Toei there was a push to start a labor movement. If I remember correctly, something like that got attempted before but the higher-ups discovered it and crushed it. Since that happened, it was a matter of being more careful the next attempt. Just like the Genroku Ako raids, we gathered and talked about it in the second floor of a restaurant. It wasn’t cool as Genroku Ako though; everyone was untidy (laughs).

But one day, when going to the company, the entrance was barricaded with lockers and we couldn’t get in. The Toei committee chairman and vice-chairman were both locked inside the company since the previous day. I had to give them some supplies but we weren’t let in. That’s when Sadao Tsukioka climbed up the fence just like a monkey, broke in, gave them some onigiri and came back. The lockout lasted around 3 or 4 days.

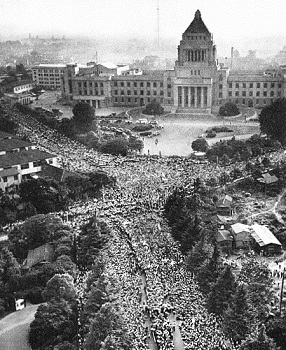

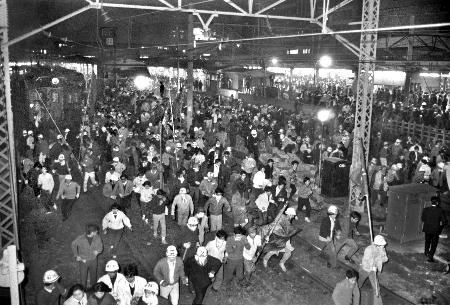

Anpo protest, 1960

Anpo protest, 1960

During that time there was the issue 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty and the national parliament was in an uproar. There was also the Federation of Cinema and Theatrical Workers Union of Japan —or the Eiensouren—, and I was told to go there so I participated. I was holding a huge flag, and we marched towards the national parliament.

When we got there, the Zenkyoutou —or the All-Campus Joint Struggle League, a radical left student group— had surrounded the parliament. We were around 100~200 meters behind them. Then a truck came by and some guys jumped off while holding lumber sticks with nails in them.

At this point he came to know the Zenkyoutou.

When you form a labor union, you can start collective bargaining. This is where the scapegoating starts. In other words, the company asks the union to do something about the guys in the blacklist or they won’t respond to their demands. At this point your own coworkers start keeping an eye on you and asking you to behave properly. I think that’s when Gisaburo Sugii gave up and went to Mushi Production. When I first met Tezuka he also told me that he wanted to make an animation studio and wanted me to come with him, so I also felt like going. If I stayed in Toei I would’ve gotten fired sooner or later anyway.

It’s not uncommon for movements that fight for rights to start having internal conflicts due to negotiations or compromises, and eventually several people might get thrown out of the movement. Considering that there are cases where the confrontation gets even stronger after compromises are attempted, judging by his description it could’ve been much worse.

As mentioned previously, even though he was given a management position he was still earning a low wage, and after getting the door shut in his face he wasn’t an enthusiastic employee anymore. The interview seems to suggest that he left Toei not because he couldn’t become a director, but because of the issues related to the labor union. Due to the frustration and the outcome of his own labor movement, he responds that they weren’t as serious as the Zenkyoutou anyway. But since labor movements not only deal with salaries but with all work-related issues, it’s not an exaggeration to say that his connection to it was fundamental.

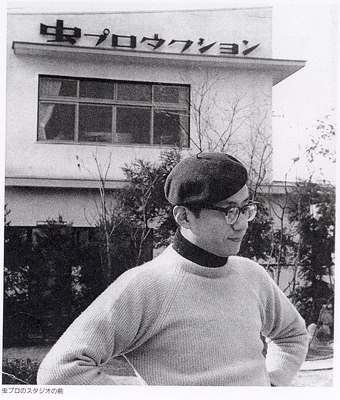

Tezuka in front of Mushi Pro

Tezuka in front of Mushi Pro

At that time Mushi Production didn’t have an income, so we were all eating with Tezuka’s royalties. When I left Toei my salary was about ¥8,000. After going to Tezuka’s place it became ¥21,000. Really big difference. At first Tezuka told me “How much do you want?”. I hesitated and didn’t reply, but then he went and said “Okay, how about ¥21,000?”.

It was before the creation of their first TV anime series, Astro Boy. By now, Astro Boy is almost seen as the symbol of going into red numbers by producing anime, but from the point of view of Mushi Production it was better than having no income at all. It’s also well-known that they didn’t profit from the work itself but from related goods and products, and it seems that the sponsor Meiji Seika improved the sales of their Marble Chocolate6.

Listening to the directors under Osamu Tezuka, it’s easy to understand that it wasn’t just him making a great salary while exploiting the rest of the staff. The reality is that everyone earned a salary worthy of their position. Looking later at the following achievements of the members of Mushi Production, Osamu Tezuka’s contributions to the anime industry are clear.

On the other hand, it’s hard to say that Toei had an adequate working environment for their staff at the time. There’s also the fact that they used the labor union to eject staff.

Reading the director’s testimonies we can’t make only Osamu Tezuka responsible for the current working conditions of the anime industry; not only people like Hayao Miyazaki —who also participated in labor unions— or Yoshikazu Yasuhiko —who’s well-known for his deep involvement in student social movements—, but also modern directors have come to work to improve things in their time.

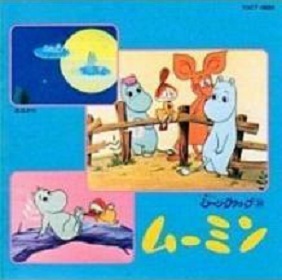

Moomin, 1969

Moomin, 1969

Later, after acquiring some experience as a Mushi Pro director, he became involved with people from labor movements.

It was when, at the request of the original author, the production of the anime Moomin —broadcasted on Fuji TV— was changed from Tokyo Movie8 to Mushi Production, in the year 1969. While he was working as the chief director, he had issues with the style of the work and the shortage of staff9. The sponsor, Calpis, had requested a “cosy” work, and after asking different people to work on the script they couldn’t come up with much. That’s when Kousaka Susumu entered the Mushi Production literary department and became in charge of Moomin. It seems Kousaka Susumu used to be in Nihon Dokusho Shinbun —a left-wing magazine—10 before Mushi Pro11.

Talking with him was fun. We talked about the Zenkyoutou and avant-garde movies. After that I told him to give us an idea. Not just a story that anyone can come up after hearing “cosy”, but more like a drama that can show the concept of family from a different perspective. He then responded: “I have one. Leave it to me.”

That’s when Kouji Wakamatsu’s Wakamatsu Production came up. At that time they were making pink films with highly erotic and political content. Kousaka introduced me to Isao Okishima. I met him and we got along well. We were the same age too.

Isao Okishima worked as the main writer for Manga Nippon Mukashi Banashi. He had still been working energetically recently by releasing his artistic SF movie, After Ten Thousand Years12.

Okishima was then unable to keep up working by himself, and he introduced the documentary maker Kunio Kurita to Rintaro. As they were making pink films, they decided to use the joint pseudonym Kuriya Okiya. The first script they worked on received good reviews. Someone from Dentsuu asked them who wrote it, but they had to hide it somehow. Rintaro himself seems to especially like episode 35.

Rintaro also asked Masao Adachi —who also came from Nihon University— to work on the script, but he replied: “Moomin is too reactionary, I won’t work on it”. Adachi later joined the Japanese Red Army.

Either way, all of this confirms that several people related to the Japanese New Left had worked on Moomin and had even made episodes related to their ideology.

Incidentally, Moomin was in the lowest 10% of the prime-time slot of Fuji TV, but only thanks to the will of the sole sponsor Calpis the show was allowed to continue. It seems they were sent Calpis as Bon festival and new year gifts so they drank it a lot. This is also when Rintaro got his first fan letter from a female student13:

There were fans of Snufkin. They were all girl students, really.

Furthermore, this was a time where the attention of adult viewers was shifting towards work creators, and a new kind of production assistants appeared:

They were all from the Roku Daigaku. The guys from Economics and Political Science of Waseda are pretty eloquent. The film studies graduates too. They first told me they had something to talk about. When I asked what’s the matter, they asked: “What is Moomin to you?”. Pretty common thing from them. I told them “Just something I work on to eat”. They replied: “Is that all?”.

At the time a book about the Sanrizuka conflict14 was very popular, and most people working on TV and movies had read it. After reading it they became really talkative indeed. They asked the same thing again; I replied “What are you planning, guys?”. It was fun. I heard most of them either became scriptwriters or went to work on documentaries.

Shinjuku Riot, 1968

Shinjuku Riot, 1968

I was drawing a storyboard in Mushi Pro, and when I turned on the TV they were reporting it. I thought it was no time for me to draw storyboards, so I took a train and went to Shinjuku. But I think I was in Takadanobaba Station when a detective pulled me out of the train. At that time I had long hair.

Having long hair was a rebellious thing for a man back then. He has short hair now.

After he was taken by the police, he told them he was an anime creator16.

When I was taken by the police, the other guys were all similar to me and were being inspected. I told them that I was working on anime in Osamu Tezuka’s company and I was released immediately. But in the end I didn’t make it to the riot. I guess I was being irresponsible, I should’ve stayed back in Mushi Pro drawing the storyboards back then.

Personally this reminds me of the case when Doraemon’s scriptwriter was taken by the police and was released when he told them he was working on Doraemon17.

I guess it was me being young. No, maybe I actually felt sympathy for the Zenkyoutou. I experienced so many things in the 60s. I saw Tadanori Yokoo nude painting on a car, girls dancing while wearing white fundoshi, performances with everyone walking like a centipede… Terayama Shuuji was there, Juurou Kara was there, Tatsumi Hijikata too. Artistically speaking it was an interesting time. While thinking how underground it was, I was making things like Nee, Moomin.

But I don’t think it all ended just as memory for him.

Adieu Galaxy Express 999, 1981

Adieu Galaxy Express 999, 1981

And later, the movie he directed in 2001, METROPOLIS. Based on Osamu Tezuka’s manga, itself based in the Fritz Lang’s movie, it deals with the issue of class struggle. In the movie, probably to portray a nostalgic world, the revolutionary leader of the armed uprising had a portrait of Che Guevara, showing the essence of the anti-establishment movement. A Ray Charles’ song was used impressively, too.

While he’s a director that doesn’t show himself much in his works, his experiences in the time of the Zenkyoutou and the Student Movement most probably are a cornerstone in them.

Finally, I’d like to finish up talking about the present of Rintaro’s career and his works.

After Moomin he left Mushi Production, but considering it was almost at the same time it went bankrupt, it was a good decision. A company with a similar name also went bankrupt at similar times so the reports often get confused, but Rintaro remembers that it was plainly due to financial problems18.

Judging just by the numbers, we were already bankrupt. Mushi Pro collapsed with no way to stop it.

Mushi Production had over 300 employees, and projects like Harenchu Gakuen also got proposed; but at the time there were comments that Tezuka’s company wasn’t suitable for them, thus they got dissolved. Still to keep the company afloat there was the necessity to take over things like Ashita no Joe and Moomin.

Everyone was leaving, but I stayed in Mushi Pro until the last minute. In Mushi Pro there was an identification card, right? So when someone left the company the numbers in the whole list got moved back. Then, when I finally left Mushi Pro and went to return my identification card, I was No.2. No.1 was the company director, Mr. Eiichi Kawabata.

If you ask me why I remained in Mushi Pro, I guess I felt we could still do something. And, as I mentioned earlier, we had a complicated history with Tezuka, so I guessed nothing would come out if I went elsewhere. I had a strong dying wish I guess, so I stayed until the very end somehow.

After leaving Mushi Pro, Rintaro was invited by his friend Atsumi Tashiro to the recently founded Group TAC19. Sugii Gisaburo was already there. Group TAC did outsorced work on Manga Nippon Mukashi Banashi, so we can guess why Okishima became the main writer. Of course Rintaro worked as a director on it and also on Yuki Onna (which got re-broadcasted recently).

Furthermore, Yoshinobu Nishizaki brought work from Mushi Pro’s last production, Wansa-kun. After talking to Tashiro, Rintaro decided not to work on it and slowly began to drift away from Group TAC. While doing freelance work and lending work on Toei anime shows and films, he later switched jobs onto Mushi Pro’s sucessor, Madhouse20, and through anime films he strengthened his artistic style and reputation.

This article is a translation of 東映・動画・手塚・労働・運動・りんたろう. Translated with the permission of the original author.

- Available on Amazon, link. [return]

- Page 29. [return]

- Page 30-31. [return]

- Also known as the Anpo. Wikipedia. [return]

- Page 32. [return]

- Page 34. [return]

- This episode wasn’t broadcasted as different mangaka took care of different cuts, ending up with a mix of different styles. But according to Rintaro, at the time it was already fixed, from the ekonte to the sakuga. Now that the film has been made public, it’s said that indeed it changed too much from scene to scene, but the interviewer says that it’s not that bad, to which Rintaro replied that if you look closely there are many weird cuts. Page 35-36. [return]

- Now known as TMS Entertainment. Since they used to change their brand name a lot, they are often called Tokyo Movie. [return]

- At the time Mushi Pro was also working on the epic film Cleopatra, which had taken most of the capable staff. [return]

- It was a review magazine from the pre-war days, but at the time it focused on reporting the New Left movement, which was considered the magazine’s golden age. [return]

- Page 51. [return]

- Isao Okishima died on July of 2015. [return]

- Page 52. [return]

- Sanrizuka struggle is the farmers’ movement that originated in 1966 and the resulting conflict and violent riots in order to stop the construction of the Narita Airport, which resulted in the death of 2 protestors and 4 police, and were well-known by then. The struggle still continues today. [return]

- In this book the date is shown as August 8th 1967, but that’s the date of the event that caused the riot, the US Army Fuel Transport Train Crash (jp wikipedia). The riot occured in October 21st, 1968. It’s not clear which one of the events Rintaro was involved in. [return]

- Page 52-53. [return]

- From Matsuoka Seiji’s “Doraemon Himitsu no Pocket”, page 205. [return]

- Page 54. [return]

- Many Group TAC members later went on to form studio Diomedéa. [return]

- Many Mushi Production members later went on to create studio Madhouse and, later, studio MAPPA; and others went on to create studio Sunrise and, later, studio Bones. [return]